Graves of African-Americans in Cedar Creek Baptist Church Cemetery

In the same cemetery where my ancestors are buried in Heflin, Alabama, countless tombstones without names can be found scattered throughout the graveyard. These unmarked pieces of stone lay above the deceased bodies of Heflin’s black townspeople. While the graves and tombstones of white people were carefully planned, the black people were considered fortunate to find a sanctioned ground to bury their loved one s. Though lacking engraved words, the plain tombstones speak volumes about the town’s shameful treatment of black American citizens.

s. Though lacking engraved words, the plain tombstones speak volumes about the town’s shameful treatment of black American citizens.

Most Americans think of racism as a problem of the past, specifically in the south; however, racism is still prominent in contemporary American society. People use crude names to classify one’s race and many gasp at the sight of interracial couples. As a young married couple, my parents decided that their children would know better than to revert to conventional, racist stereotyping. I was taught from a young age to look beyond what the world perceives as different and judge only by the character of one’s heart. Not only were my parents wonderful teachers in this respect, but all four of my grandparents have set great examples regarding acceptance as well. Because this teaching has been prevalent throughout my life, I was both shocked and intrigued to learn about the racism from my mother’s lineage.

My great-grandparents, William and Cora Coefield, had ten healthy children: seven girls and three boys. With so few boys, the girls had to work right alongside their brothers in the hot Alabama sun. The sun burned and freckled their pale white skin, but sharecroppers’ children never quit until the job was finished. As the sun beat down on BF Coefield’s back each day, his eyes shifted toward the fields where the “colored folks” picked cotton. Day after day his resentment towards them grew and in his heart festered a deep, dark dislike. BF Coefield (my grandfather) felt as worthless as the dirt on his worn, hand-me-down shoes for the majority of his life. So he held tight to the lie that he was more important than black people in order to find pride in himself. This lie proved simple to believe. His parents taught him not to harm black people, but to “let them be” because “they had their place.” This racist belief was only to be expected from his deep roots in Heflin, Alabama. After all, Cleburne County (Heflin’s county) researcher, Ross Stewart, reveals that the small town of Heflin was founded in 1850 as a place to “bring the swift negroes to Alabama” (74). A town founded on such racist principles takes many generations to overcome.

As BF grew older, his days working for his father in the field came to a close. BF began working in a KFC chicken factory, and soon after married the love of his life, Jane McLeroy. Together the two raised a son and a daughter in the ways of the south: work Monday through Friday, rest on Saturday, and go to church on Sunday. After a church service in 1968, BF accepted Christ as his Lord and Savior, and Christ immediately began working in BF’s heart. Southern-Baptist-classified sins, such as drinking liquor, were of no trouble for transformed BF to abandon. However, the sinful nature of racism was not a topic of discussion in churches. For years after becoming a believer, BF never questioned his stereotypes toward black people. God would change BF’s prejudiced heart over time.

Above: My sister, Amy, and her husband, Michael Nichols Below: Lucy and Marx Gary’s three daughters, my nieces

BF and Jane became involved in many different ministries and after many years of ministry work inside the United States, they ventured overseas. In 2001, they settled in Tanzania, Africa for long-term mission work with the Here’s Life Africa missionary campaign. Although he had worked in America with people of all different races, it was not until his work in Africa that my grandfather began realizing that the color  of one’s skin has no effect on his or her worth. He finally understood that his light skin tone made him neither more nor less significant than those with dark skin tones. Once he saw the truth he had been blinded to, he was ashamed of his sinful, self-righteous thoughts towards black people, and he had an immediate change of heart

of one’s skin has no effect on his or her worth. He finally understood that his light skin tone made him neither more nor less significant than those with dark skin tones. Once he saw the truth he had been blinded to, he was ashamed of his sinful, self-righteous thoughts towards black people, and he had an immediate change of heart

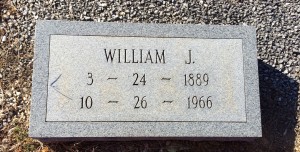

In 2007, my sister and her black fiancé were married by my grandfather. His support for their marriage displays a beautiful picture of his transformation. In 2012 another sister of mine married a black man. When people come to know that I have not one, but two African-American brother-in-laws, eyebrows are raised, questions are asked, and assumptions are made. My family members and I have grown immune to the reactions from people. My sisters’ interracial families stand as a beautiful picture of how far my family has come from its racist roots. Any trace of racism remains in the past – buried with my great-grandfather, William Jefferson Coefield.

Frank Ross Stewart. Alabama’s Cleburne County: A History of Cleburne County and Her People. Centre, Al: The Stewart University Press, 1982. Print.